One Struggle, Many Fronts Speaking Tour

All of us in Maypop work part-time jobs in order to fund our work with Maypop. We’ve worked at farmer’s markets, cheesesteak shops, and non-profits. For the last six months, I’ve been fortunate to have a position with the US-Africa Network (USAN), a national organization that connects progressive social movements in the United States and many African countries. USAN is a new organization, but its founders have been supporting African peoples’ movements since the 1960s.

My job was to organize a national speaking tour with two African climate justice activists. After months of planning, the tour happened from March 20 through April 3. Our guests of honor were Emem Okon from the Kebetkache Women’s Development and Resource Centre in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, and Mithika Mwenda from the the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance, based in Nairobi, Kenya.

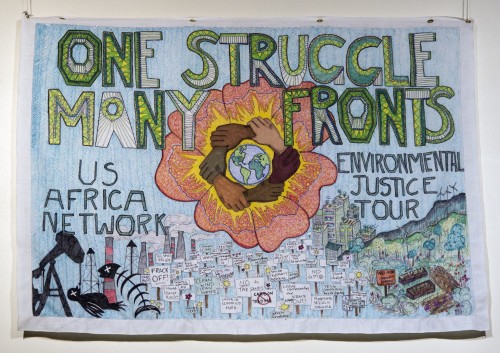

The tour visited Washington DC, New York City, Detroit, Kalamazoo, Chicago, Oakland, and Atlanta. We spoke with three types of groups: community-based environmental justice organizations, student fossil fuel divestment activists, and Pan-African and African solidarity activists. To honor the diversity of climate justice work happening in the US and Africa, we called the tour One Struggle, Many Fronts.

Watching Emem and Mithika speak and interact with our hosts and audiences day after day was like going to school, in the best possible way. I’d like to share a few stories and lessons that stick with me.

The True Face of Corporate Power

Emem Okon uses popular education workshops to empower women to resist oil drilling in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Since 1956, the 31 million residents of the Niger Delta have suffered under the rule of Chevron, Shell and ExxonMobil. They have experienced the equivalent of 50 Exxon Valdez oil spills, none of which have ever been cleaned up. Military interventions have killed tens of thousands of civilians in the same period.

Emem described all this, complemented by the film Poison Fire, but I struggled to comprehend it. How could this be possible? The brutality of the oil companies in the Delta didn’t align with even my dim view of their morality. I was finally forced to overcome my denial. Repeat after me: This is really happening.

How can it be happening? Many reasons. The government has little desire or ability to stop the corporations, and the people don’t have effective democratic mechanisms to assert their will. Racism and colonial legacies are central to this story. Our media in the North decide that black Nigerians losing their livelihoods, getting sick, and being killed by the thousands is not newsworthy. The result is that the corporations have free reign to continue their abuses.

In the Delta, we see one of the purest expressions of corporate power. They pollute and kill, because it is profitable, and because they can.

We should pay attention to the Niger Delta because the people there are human beings who deserve so much better, and are courageously fighting back. We should also pay attention to learn and re-learn the simple lesson that Exxon, Chevron and Shell do not care about human life. Once we learn this lesson, and remember that these very same corporations operate in the United States, we are forced to admit that it could happen here, too.

Oil companies are already exploiting communities across the U.S., but not on remotely the same scale. The main thing standing between us and a Niger Delta-like situation is the thin layer of democratic protections that we have won in this country. We need to fight to expand these protections. We also need to recognize that racism, class domination and colonial legacies are also at work within the United States, and prioritize our efforts with the communities for whom the democratic protections are thinnest.

In the long run, though, even democratic protections against corporate power are not enough. Corporations are too dangerous to restrain permanently; they must be destroyed. They are made of human beings, yet they behave in profoundly inhumane and inhuman ways. Left uninhibited, as in the Niger Delta, they extract every drop of wealth from land and labor. They destroy ecological systems, displace human communities, and kill all dissidents.

The corporation, as a form of social organization, needs to go. That’s one lesson from the Niger Delta.

Nonviolence as a Feminist Response to Ecological Crisis

In the early 2000s, young men in the Niger Delta formed a violent resistance group called Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND). MEND’s primary tactics are sabotage of oil facilities and kidnapping of oil workers. Some U.S. activists invoke MEND as an example of a group using justified violence when other strategies have failed.

Emem told a different story. From her point of view, MEND has made things worse rather than better. Sabotage and kidnapping led to a government military intervention, in which women suffered uniquely. Men killing men caused many women to lose their husbands and their sons. Both sides in the fighting committed sexual violence against women. Things finally deescalated when the government bought out large numbers of the violent youths, which they continue to do. This money never makes it to the community women.

In the film Poison Fire, an elderly activist named Comrade Che says of MEND and the oil companies, “Violence attracts violence. Peace attracts peace.” The corporations brought violence to the Niger Delta, and they bear the most blame. But this doesn’t release MEND from responsibility for its actions. Nor does it release activists in any other part of the world who make the same decisions.

Emem’s experience is that violence is a blunt tool for social change. It can destroy symbols of oppression, but it also destroys people, families and neighborhoods. When good things are destroyed, it is usually women who have to pick up the pieces and rebuild.

This is why Emem is a strong believer in direct, nonviolent resistance, led by community women. The women Emem works with have done amazing things in opposition to the oil industry. To give only one example, in 2002, hundreds of women occupied a Chevron oil terminal for eleven days, eventually winning concessions from the company. This action got the goods, without the collateral damage of violent tactics.

Unite, unite, unite!

Mithika Mwenda is the Secretary-General and co-founder of the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance (PACJA), which includes approximately 1000 member groups from across the continent. PACJA operates at the local, national, and international levels, including the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiation process. Mithika advocates for responses to climate change that prioritize the sovereignty and wellbeing of poor people in Africa and the Global South.

The most striking part of Mithika’s message, to me, was his repeated insistence that we unite our movement across geography and issue boundaries. I was taken aback to realize that I rarely hear calls for unity among progressive groups in the U.S.

There are good reasons for this. So many coalition-building attempts have already been doomed by egos, funding priorities, hubris from big groups, and just plain busyness. It’s hard to unite. But it’s even harder to imagine that we will create a just response to the unfolding ecological and economic crisis without coming together. We are talking about a paradigm shift, a revolution of values and power relations. We are talking about changing the way we work, the way we produce food, the energy we use, the way we relate to each other, and so much more. Isn’t it obvious that this will require unity?

Mithika doesn’t ignore any of the barriers to unity. He faces the same organizational challenges in Africa that we face in the U.S. What he has is an unshakable conviction that unity is both necessary and possible. When I hear him, I don’t forget about the problems, but I start focusing on solutions. I think…

We’ll build our alliance from the grassroots up, in order to prevent big national organizations from throwing their weight around early on.

In each place, we’ll continue organizing around the issues most relevant to us, in language our people understand. We’re also going to start challenging each other to find strength in unity, and understand the relationship between the “many fronts” of the “one struggle.”

We’ll use every opportunity to educate the public about ecological crisis and the just transition.

We won’t waste our time in arenas that have no potential for us. That said, we’ll find strategic opportunities to contest for governmental power at the local, state, national and international level. Over time, our mass organizing will enable us to win more and more of these contests.

Every day and every conversation, we’ll help more people believe that real unity and revolutionary power is possible.

This is how Mithika approaches his work. His energy and grounded optimism is inspiring me to continue breaking down issue and organizational barriers through my work with Maypop.